Since the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT for the public, AI has rapidly moved to mainstream discussion. The chat bot, which is only a small piece of its AI revolution, is designed to create natural conversational dialogue in response to a user’s prompt. Over the past year, people all over the world have begun to use it along with other AI services to write articles, emails, and even code. Perhaps the most discussed use of this technology is that of students to complete essays and other writing assignments. Alert to the significance of generative AI in education, Plymouth South faculty met to address these recent changes.

The presentation was given by Greg Kulowiec, the Technology Director at Triton Regional School District, and a co-founder of the Kulowiec Group—a tech consulting organization for schools. According to Ms. Fry, before Mr. Kulowiec was helping schools rethink education as technology develops, he was “a tremendous social studies teacher” and basketball coach at our very own Plymouth South. On September 13th, he returned to discuss the impact and implications of AI on education on both teachers and students.

AI In Education

What is AI anyway, besides a scary new word? Artificial intelligence (AI) is a computer’s ability to perform tasks that are otherwise associated and performed with human intelligence: Making complex decisions, perceiving images, recognizing speech, you name it. Generative AI specifically, like ChatGPT, is concerned with the production of new content—writing, images, videos, and audio.

While previous technological revolutions brought new power to the wealthy and powerful, the advent of AI is different. AI is for anyone. Anyone with internet access can generate music with Mubert. We can make images with DALL-E. We can use ChatGPT to produce a short story in a matter of seconds. We can research scientific articles with PerplexityAI, and then use Github’s Copilot to write code.

This accessibility has made AI everyone’s business, including students and teachers. With the popularization of ChatGPT, high school and college students quickly began to outsource their homework to technology. In fact, a survey by Intelligent.com revealed that almost a third of college students used it to complete schoolwork for the last academic year, a figure that can only be expected to grow. Teachers, in response, have been on the lookout, with plagiarism checkers that have likewise begun to adapt for the new world.

Yet, these tools are undeniably imperfect: When a Furman University professor, Darren Hick, encountered an allegedly student-written passage that was flagged for AI, he could find no citations or definite proof. It’s true that a handful of detectors are somewhat accurate, but a lack of certainty makes their use in disciplining cheaters challenging. The philosophy professor fears that the future will hold fraudulent work from students that he and his colleagues will struggle to prove as such.

Students, on the other hand, have different concerns. Not only do students who use AI for writing assignments risk getting caught, but those who don’t are now under the threat of false accusation by educators who are overconfident in the accuracy of detectors. There’s no shortage of complaints online. “He still does not believe me,” reads one post on an online forum to discuss ChatGPT. “How can I prove my innocence?”

The Impact on Students

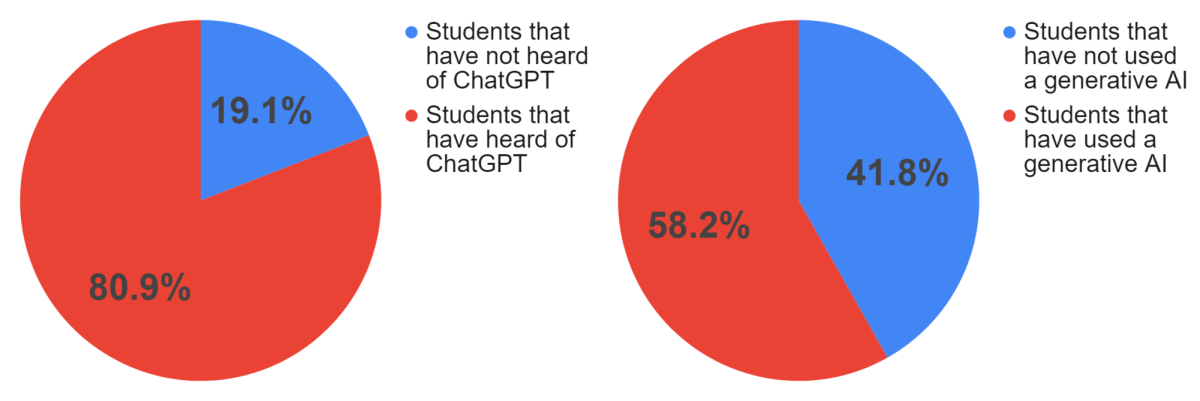

A global impact is evident, but how has AI impacted students at Plymouth South? Are students cheating, or exploring? Has there been a school level impact at all? To answer these questions, a survey of 288 students was conducted. Students were asked about whether they’ve heard of ChatGPT, whether they have used it or a similar generative AI, what their use involved, and any other comments they wanted to include.

The presence of AI in the lives of Plymouth South students became clear: For every five students surveyed, only one has not heard of ChatGPT. In fact, well over half of the sampled students admitted to having used ChatGPT or other generative AI. For good or for bad, AI has a broad influence on students.

So how exactly are students using it? Very diversely. While some students only use generative AI out of interest, others are getting as much use out of it as possible. Many view it as a way to relieve the load of school work. One senior describes his experience with using ChatGPT for writing essays, saying “I’ve score[d] 80/100 points on essays using it.” A junior was more blunt: “It’s great, it helps me cheat my way through high school.” Yet, many others instead said that AI “freaks me out” and it’s “really scary,” or that it’s “garbage” that “encourages laziness.”

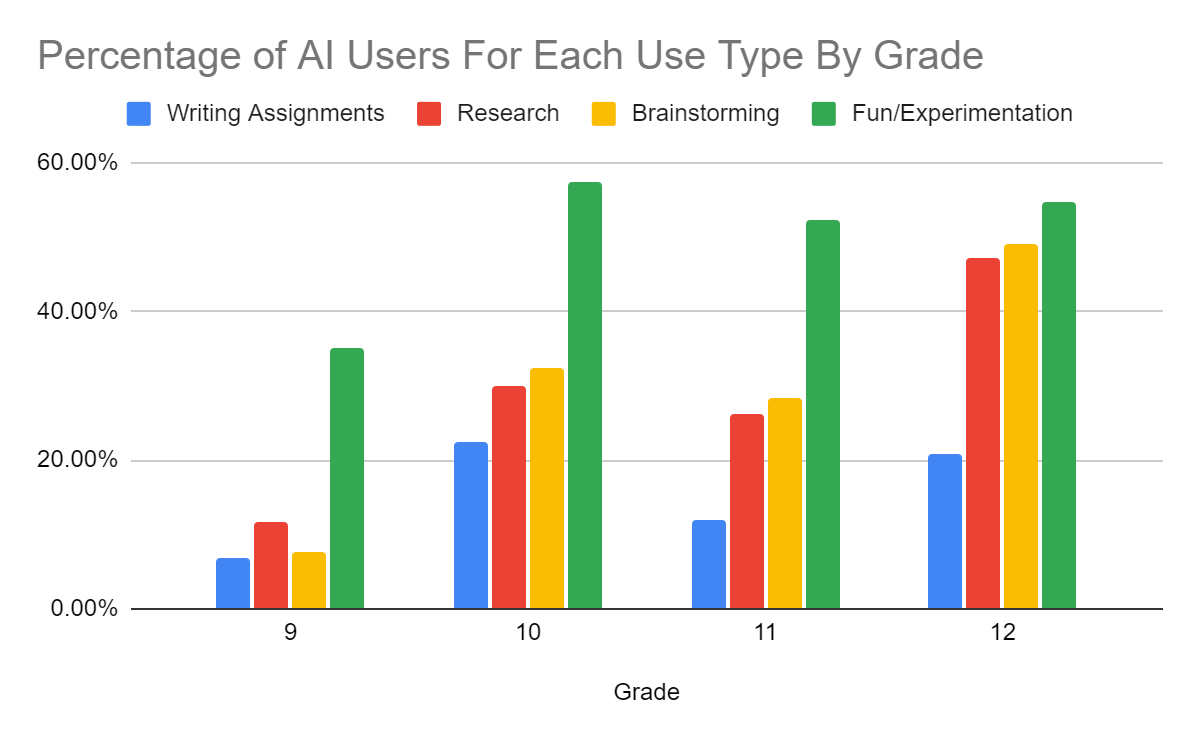

Dozens of the students that volunteered to leave an extra comment differentiated their opinion on AI based on how it is being used. A common sentiment was, as one student put it, “students should be able to use if it is giving resources but not to write essays.” Another said that “it’s more of a learning tool.” A handful of students also regarded it as a way to tackle confusion, “if I am having trouble with something.” These more nuanced takes weren’t just a handful of students, but voices for the larger student sentiment reflected in the survey.

In accordance with the idea of limited use, a significant number of students are actually using it productively. In fact, the data clearly indicates students using generative AI for research, brainstorming, and experimentation at much higher proportions than for writing their assignments for them. Four out of every five students who have used generative AI claimed to only use it for these purposes and never for writing assignments. It seems that for this group of students, AI is something to support their education rather than to replace it. One student even suggested AI as not only a helpful part of education, but a necessary one, noting how “People use AI already in the professional world so it is important to learn how to use the AI.”

Admittedly, the survey is not a perfect representation of the student body. Of the advisory classes that participated, it’s likely that specific students chose not to respond. Regardless, the results have revealed that student sentiment is diverse, and at least a sizable percentage of students have found a balance between using AI to cheat and not using it at all: Productive use.

Admittedly, the survey is not a perfect representation of the student body. Of the advisory classes that participated, it’s likely that specific students chose not to respond. Regardless, the results have revealed that student sentiment is diverse, and at least a sizable percentage of students have found a balance between using AI to cheat and not using it at all: Productive use.

The Perspective of Teachers

Ms. Fry had revealed her supportive attitude towards AI even before the meeting. Instead of tackling AI as a problem, the presentation was “to share some of the positive approaches to this amazing tool and how we can embed it in our courses.” Accordingly, Kulowiec’s presentation conveyed an optimistic perspective on AI use: This technology could be a resource for both students and teachers.

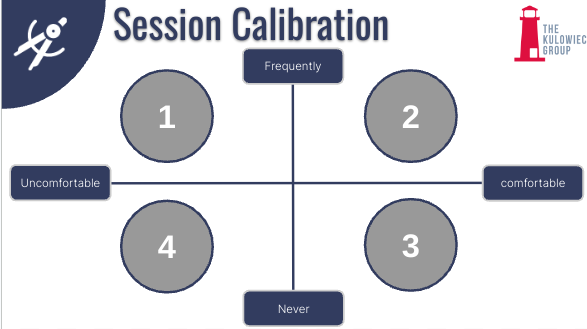

According to Kulowiec, faculty would be brought up to speed on AI “beyond ChatGPT,” with practical and interactive activities over their two hour stay. Teachers were prompted to try various techniques to generate more useful responses, as well as to share their perspective at various points. For example, early on in the meeting, Kuloweic requested a show of hands to determine exposure and comfort of teachers surrounding AI.

In an informal vote, a significant number of faculty members indicated both discomfort and little to no use, while no one was noted to indicate frequent use and comfort with the technology. Kuloweic thereby revealed the stark difference between students and teachers at Plymouth South. While most students had integrated AI in some way into their lives, the majority of teachers had not. The presentation then went on to work towards changing this, as Kuloweic demonstrated an array of different AI tools and suggested possible uses for creating educational material.

He then went on to teach more effective use of ChatGPT, covering various prompt writing concepts. More generally, he supported thinking about how education can be enhanced using artificial intelligence as a resource and thought partner for teachers. Kuloweic compared the skill of AI use to searching the internet. Just as better users of search engines like Google are advantaged, so are better prompters of generative AI. In the next show of hands, many of the teachers agreed that they had gained a broader perspective than they had before the start of the meeting.

The school’s technology integration specialist, Mr. Schuler, shared his perspective in a brief interview a few weeks later. Mr. Schuler believes that AI has a place in education, however, he remarked that access is “so limited due to age restrictions.” Still, he believes that “introducing it at an appropriate age” and teaching productive use is a great place to start. “The problem is that many users will be using it prior to, and start using it in ways that probably aren’t as beneficial in education.”

An English teacher at South, Mr. Lippa, spoke on his own approach to addressing AI, reflecting the attitude of students and the rest of faculty: Disapproving of “heavy-lifting” by AI, but also favoring a limited use. “I want to use it in the revision process, so they know how to use it as a tool,” he explained.

In an effort to achieve this balanced use from his students, Mr. Lippa uses detection services to identify inappropriate cases of AI-use, after which he has a private conference with the student. He first hears their process, as oftentimes the student’s intention is not to cheat. Then, he “give[s] feedback on how to use it as a tool to help them.”

Mr. Lippa’s use of software for detecting AI-generated text calls into question issues with reliability that Professor Hick experienced. Given their imperfection, what can be done for students who are detected by the software but insist that they are innocent? At this point, detections are treated as cases of plagiarism. “We don’t have a clear protocol, and we need that.”

The Future of AI At Plymouth South High School

To achieve better clarity, a meeting of department heads in the district and central office administration was organized for November 17th. According to Mr. Schuler, the meeting was planned to explore AI capabilities, implications for teaching and learning, as well as policy. “The hope was for this discussion to lead to the unblocking of ChatGPT.” Ultimately, the meeting was indefinitely postponed.

This development has brought Plymouth South’s rapidly developing relationship with artificial intelligence to a halt. While Mr. Kulowiec has boosted the use and understanding of AI among teachers at South, ChatGPT remains blocked for students on their school-issued Chromebooks. Yet, students continue to use it on their own devices in unregulated and diverse ways. What becomes of student and teacher perspectives and policies on artificial intelligence in education, and in Plymouth South High School, remains to be seen. In any case, AI will continue to have influence—good or bad.